Nackles by Donald Westlake

The Twelve Slays of Christmas 2013

For the sixth slay of Christmas, this genre gave to me, the anti-Santa Nackles, BILL GOLDBERG!, four creepy songs, Tales from the Crypt, enslaved demon Krampus, and a scream queen hanging free!

Today we are getting literary again with another short story based on a Santa-like construct that punishes the naughty. Nackles is the anti-Santa Claus, and he originates in Donald Westlake’s (writing under the pseudonym Curt Clark) story “Nackles” published in 1964. The evil Santa in this story is a bit different than what we’ve encountered before. While Krampus is a black-hearted demon enslaved by the righteous and more powerful Saint Nick, Nackles is an entity of equal power driven by an opposite motive. Also, whereas Goldberg plays his Santa-as-really-a-demon to comedic effect, Nackles is much more cerebral and mysterious.

Nackles is the evil alternative of Santa being not just an angelic being, but a godly one. This is a story that questions what Christmas has become in our modern society, with Santa as “a god of giving, of merchandising, and of consumption.” It also explores where the tenacious ideas of god and religion come from in the very first line: “Did God create men, or does Man create gods?”

Nackles may be a more modern antithesis to Santa Claus than Krampus, but he is no less outwardly grotesque. He is “very very tall and very very thin. Dressed all in black, with a gaunt gray face and deep black eyes. He travels through an intricate series of tunnels under the earth, in a black chariot on rails, pulled by an octet of dead-white goats.” From this description, Nackles seems almost to be a holiday version of Slenderman!

flickr / Chris Isherwood

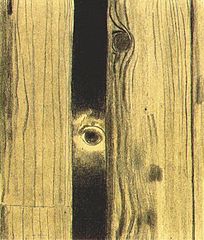

He sees you when you’re sleeping . . .

The story of Nackles was at one time being developed by George R. R. Martin and Harlan Ellison as a holiday episode of the 1980s Twilight Zone reboot. Unfortunately, it never came to fruition. Nackles is the perfect entity to exist in the Twilight Zone, as he is a fantastical creation brought to life (?) by the power of imagination. Millions of people believe that Santa Claus is real, and those of us enlightened folks (adults) go along with the whole schtick too. So, if we give lip service to a Santa, why not a Nackles?

You can read Donald Westlake’s “Nackles” in its entirety by clicking here.

You can read more about the Nackles Twilight Zone debacle by clicking here.

I’ll be back with another Slay of Christmas real soon. Until then, don’t be naughty!

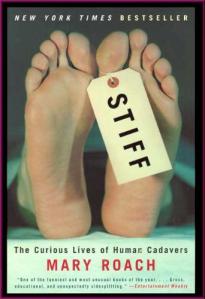

12 Options for Your Body once You’re Stiff

Mary Roach‘s Stiff is a very enjoyable and often humorous read about what happens to people who’ve donated their bodies to science. It’s an interesting take on the past, present, and future of cadaverous research that also takes funny diversions towards other morbid curiosities. Given the grim subject matter (death & body disposal) one assumes that this would likewise be a grim read. But one would be wrong. Roach is deft in her lighthearted tone, and she infuses the topic with levity while maintaining a certain respect for each deceased individual she encounters. To give you an overview of each chapter, as well as a tasty morsel of Roach’s writing, I’ve highlighted each of the book’s twelve chapters in this list of things that could happen to your body once you’re stiff.

1. Your head may be lopped off and used as a model for plastic surgery lessons.

Only they’ll leave the skin & flesh on.

flickr / Pieter Cornelissen

flickr / Pieter Cornelissen

The heads look like rubber Halloween masks. They also look like human heads, but my brain has no precedent for human heads on tables or in roasting pans or anywhere other than on top of human bodies . . . (p. 23)

2. While the history of using corpses for medical research is a long and sordid one, you need not worry about being snatched from the graves. Today’s researchers don’t dirty their hands with shovels, and the subdued decorum of a modern anatomy lab is much different than those of early predecessors.

wikimedia commons / The Reward of Cruelty by William Hogarth

wikimedia commons / The Reward of Cruelty by William Hogarth

Engravings by Thomas Rowlandson and William Hogarth of eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century dissecting rooms show cadavers’ intestines hanging like parade streamers off the sides of tables, skulls bobbing in boiling pots, organs strewn on the floor being eaten by dogs. In the background, crowds of men gawk and leer. (p. 47)

Evidently, compassion for cadavers wasn’t discovered until sometime in the early twentieth century.

wikimedia commons / Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine 1908 Dissection Lab

wikimedia commons / Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine 1908 Dissection Lab

3. You could go to the body farm behind the University of Tennessee Medical Center, where corpses are kept in varying states of decay (and varying states of undress, varying burial depths, etc.) to study how different disposal methods affect the body and aid the work of criminal forensic investigators.

wikimedia commons / Strickwerker

Scientist Grover Krantz spent part of his after life on the body farm. Clyde, his dog, however was buried in his yard.

“You want a vivid description of what’s going through my brain as I’m cutting through a liver and all these larvae are spilling out all over me and juice pops out of the intestines?” (p. 63) — forensic research professor Arpad Vass

4. Your corpse could be used in a car crash tests. While dummies are good for taking a licking and keeping on ticking, nothing demonstrates an automobile’s effect on humans like a dead human.

flickr / perthhdproductions

flickr / perthhdproductions

This never would have happened with someone living behind the wheel.

But let’s be rational. Why is it okay for someone to guide a table saw through Granddad’s thigh and then pack the leg up for shipment to a lab, where it will be suspended from a hook and impacted with a simulated car bumper, yet not okay to ship him and use him whole? What makes cutting his leg off first any less distasteful or disrespectful? (p. 105)

5. Cadavers were once thrown from planes to study the effect of plane crashes on the human body. While this wouldn’t happen to your corpse nowadays, aviation crash investigators do have a term for bodies found at a crash site — ‘human wreckage.’

flickr / Tom (shock264)

flickr / Tom (shock264)

As far as I know, there’s no special term for crop wreckage.

For unlike a wing or a piece of fuselage, a corpse will float to the water’s surface. By studying victims’ wounds — the type, the severity, which side of the body they’re on — an injury analyst can begin to piece together the horrible unfolding of events. (p. 114)

6. Perhaps you’d like to join the army! There has been a lot of work with cadavers in the field of military research. While some research is done to find more humane weapons than lead bullets (which expand on impact and destroy more flesh), most militaries want weapons with the maximum stopping power, i.e. most damaging / the least humane.

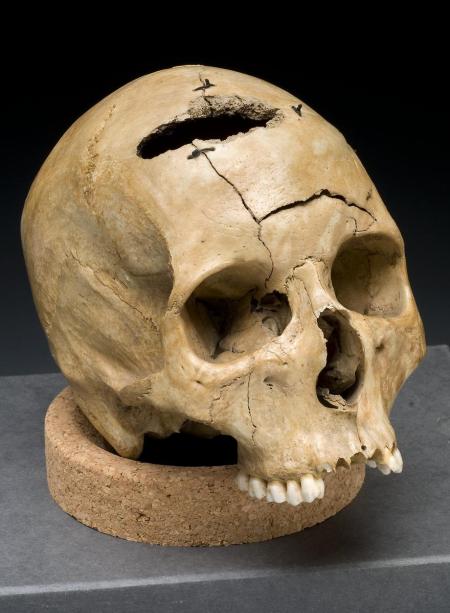

wikimedia commons / Civil War Collection, National Museum of Health and Medicine

wikimedia commons / Civil War Collection, National Museum of Health and Medicine

Ballistics studies are especially problematic. How do you decide it’s okay to cut off someone’s grandfather’s head and shoot it in the face? (p. 147)

7. Be glad that you’re not a French stiff from 80 years ago. In the 1930s, a doctor in France named Pierre Barbet crucified a corpse and several severed arms in an attempt to authenticate the Shroud of Turin.

wikimedia commons / Johnny Hillerman

wikimedia commons / Johnny Hillerman

In the weeks that followed, Barbet went through twelve more arms in a quest to find a suitable point in the human wrist through which to hammer a ⅓-inch nail. This was not a good time for vigorous men with minor hand injuries to visit the offices of Dr. Pierre Barbet. (p. 160)

8. Despite persistent urban legends, there is no ‘cellular memory’ in the organs of the dead transplanted on or into the living. Fortunately, your personality won’t change if you get the parts of a madman. Unfortunately, your heart may still be beating in someone else, but it won’t be ‘your’ heart.

Paramount Pictures / poster for Body Parts

Paramount Pictures / poster for Body Parts

In light of recent facts, the believability of this film is further strained.

Mehmet Oz (YES, THAT DR. OZ), the transplant surgeon I spoke with, also got curious about the phenomenon of heart transplant patients’ claiming to experience memories belonging to their donors. “There was this one fellow,” he told me, “who said, ‘I know who gave me this heart.’ He gave me a detailed description of a young black woman who died in a car accident. ‘I see myself in the mirror with blood on my face and I taste French fries in my mouth. I see that I’m black and I was in this accident.’ It spooked me,” says Oz, “and so I went back and checked. The donor was an elderly white male.” Did he have other patients who claimed to experience their donors’ memories or to know something specific about their donor’s life? He did. “They’re all wrong.” (p. 191)

9. Research on just-guillotined criminals progressed to dogs and later monkeys. While a human head transplant has never been attempted, it is theoretically medically viable — although you’d still be ‘just a head on a pillow.’

American International Pictures / The Brain that Wouldn’t Die

American International Pictures / The Brain that Wouldn’t Die

By putting them — their heads — onto new bodies, you would buy them a decade or two of life, without, in their case, much altering their quality of life. High-level quadriplegics are paralyzed from the neck down and require respiration, but everything from the neck up works fine. Ditto the transplanted head. (p. 212-213)

Here is a video of neurosurgeon Dr. Robert White explaining the procedure:

10. Perhaps you’d like to be consumed upon death. Just about every part of a dead body has been used as ancient medicinal or folk remedy. Blood is especially popular, both for drinking and bathing.

flickr / rachel a. k.

flickr / rachel a. k.

It was when the prescription called for bathing in the blood of infants, or the blood of virgins, that things began to turn ugly. The disease in question was most often leprosy, and the dosage was measured out in bathtubs rather than eyedroppers. . . . We see nothing distasteful in injections of human blood, yet the thought of soaking in it makes us cringe. (p. 226&9)

11. If burial or cremation bores you, then you may be interested in other ways a body can be disposed of after death. There is freeze-drying and composting, as well as the newly developed method of ‘water reduction,’ more grimly named ‘tissue digestion.’

flickr / Francisco Javier Argel

flickr / Francisco Javier Argel

Just don’t accidentally drink Grandma.

In a few hours . . . [the] equipment can dissolve the tissues of a corpse and reduce it to 2 or 3 percent of its body weight. What remains is a pile of decollagenated bones that can be crumbled in one’s fingers. Everything else has been turned into . . . a sterile “coffee-colored” liquid. (p. 252-253)

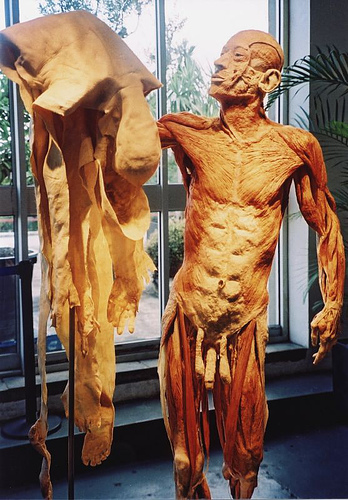

12. Maybe you want your corpse to last 10,000 years. In that case plastination is the only surefire way to make sure your corpse stays fresh for millennia. All of the water in your body is sucked out during an acetone bath, which evaporates, and then is replaced by a liquid polymer.

flickr / Paul Stevenson

flickr / Paul Stevenson

Is it a little chilly in here, or is it just me?

Like a guinea pig the size of a police dog, the concept of being plastinated is more unsettling than the reality. You just lie there, soaking and plastinating. Eventually, someone lifts you out and poses you, much as one poses a Gumby. A catalyst is then rubbed into your skin, and a two-day hardening process begins, working its way through your tissues, preserving you for all eternity in your freshly dead state. (p. 289)

While not everyone would like to be naked and skinless for thousands of years, perhaps you’ve found something to do with yourself after ‘yourself’ ceases to exist. In the meantime, go out and pick up a copy of Stiff by Mary Roach. This book is a fun and enlightening read filled with many more quips than I’ve excerpted here. It’s a shining bit of amusement among death’s pieces of darkness.

Links

Click for more information on Tissue Digestion.

Click for more information about The Body Farm.

Click for more information about Dr. Pierre Barbet’s corpse crucifixion experiments.

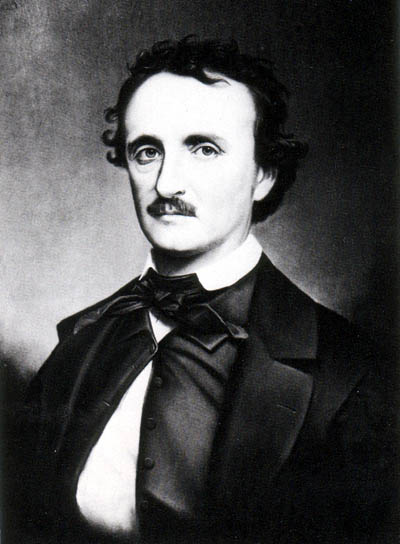

How “The Tell-Tale Heart” Ticks

Although the graphic sights and sounds of the horror movies glisten more vibrantly than the written word, the Halloween season is a great time to revisit horror fiction. One of my perennial favorites to read this time of the year is Edgar Allan Poe, whom no genre fan is a stranger towards. Poe was not just a superb storyteller in the realm of horror, but his work stands as that of a master craftsman in the (relatively new for his time) art of the short story. Just as movies have tighter narratives and less lag than a serialized, weekly TV programs (see The Walking Dead’s second season), so too is a short story is able to vividly portray a terrorific jolt while remaining in the confines of a few pages. This shorter form constricts the writer to a more economical with his words than a novelist. But, while it meant that Poe’s stories would be stripped any superfluous language, the essential details would remain clear and a singular chilling moment would be distilled to haunt the reader’s imagination.

A perfect example Poe’s craftsmanship and economy of language is “The Tell-Tale Heart,” which at a mere 2000 thousand odd words, is short and to the point. Now, while the tale’s brevity may make it more appealing to modern readers, what makes this an effective horror story that has stood the test of time is Poe’s pacing and use of repetition in his writing. Although some of Poe’s other stories, such as “The Cask of Amontillado” and “The Black Cat,” would also feature murderous narrators retelling their evil deeds, it is my opinion that “The Tell-Tale Heart” establishes this maniacal fiend not only the best in Poe’s body of work, but probably in the entire canon of dark fiction.

Before diving into what makes “The Tell-Tale Heart” tick, have a look at the story’s opening paragraph:

TRUE! –nervous –very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses –not destroyed –not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How, then, am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily –how calmly I can tell you the whole story.

Again, the two key elements that make this story so effective — pacing and repetition — are both present from the opening lines. From the onset — from the very first word — the pacing is quick. This narrator’s mind and heart is racing, and the reader speeds along with him, not only because of the words that Poe chooses — “nervous/dreadfully/disease/sharpened” — but also because of the internal rhythm of the sentences he constructs. Each word is a short explosion — a hammering — punctuated only by the next. This is not some Lovecraftian lugubrious and slowly unfolding story, this is Edgar Allan Poe at his most frenetic and fanatical. Consider how the exclamation point after the first word bursts forth from the page. Consider how the next word — nervous — is not recited simply as a matter of fact, but as a condition of being. No one calmly says that they feel nervous, no, this word bounces off the page as an actor, or a murder would actually speak it. There is a stuttering in this text, but it further serves to quicken the pace. Read the next word — very — and there is a comma afterwards telling you to stop, to slow down, but that is all too much as you are already sucked in. The words move more quickly now, pausing only momentarily at the semicolon, and then racing off to the question mark, where, despite the narrator’s pleas to be considered mentally sound, the reader has likely already reached the sobering realization that he is unreliable, if not altogether off his rocker. The second sentence continues this frantic pace, all while reaffirming to the reader that this man, claiming to have been imbued with superhuman hearing following an act of murder, is certifiably insane.

It isn’t just punctuation or word order that contributes to the quickened pace, but also the very words themselves. All of them are short. In this opening paragraph there is not a single word longer than three syllables. Neither the narrator’s, nor the reader’s heart is at rest, and neither can simply plod through the text. These are hearts under stress, and although the shorter syllabic structure makes the reading more rhythmic, it also serves to speed things up. The narrator’s palpitations are palpable to the reader because of Poe’s control over the pacing of “The Tell-Tale Heart.” Naturally, Poe pulls back as he eases into the rest of the story, but it is interesting to note how he starts this tale with the same heart-pounding pace as the horrific reveal at the finish.

As with pacing, repetition is something that Poe could could use very, very effectively — see “The Raven,” and especially, “The Bells.” In “The Tell-Tale Heart” the first sentence contains repetition of the words ‘very’ and ‘nervous.’ Our dear narrator isn’t just nervous — he isn’t even just very nervous — he is nervous, very, very dreadfully nervous. Poe’s repetition isn’t confined to just repeating words, as starting from the second line Poe uses a repeating sentence construction: not destroyed –not dulled and continues on with repetitious sentences: I heard all things … I heard many things. What does this repetition serve? It ties the reader closer to the subject matter as we are compelled to feel as the narrator feels. We are hearing the same thing, in our head, over and over again, just as the narrator is hearing, over and over again, incessantly, maddeningly, that beating of the dead man’s heart.

Poe’s language heightens the reader’s sense of awareness as one falls in line with the narrator’s speech pattern. This is deliberate, to make your heart speed up and to make you short of breath with the heavy H sounds in the last few lines of the opening. Speak them out loud yourself. These are heavy, breathy sounds — hearken, how healthily, whole story — and they serve to slow the pace as the narrator, and you the reader catch your breath from the fantastic opening of the story.

And what a story it is! “The Tell-Tale Heart” is as archetypal and influential as any other in the genre of horror. This horrific Halloween holiday season, I would urge you to get back the roots of horror and rediscover one of the monumental pillars of the genre (and all of fiction). Go and pull your Poe off of your bookshelf (any self-respecting horror fan ought to own a tome!) and revisit “The Tell-Tale Heart”. Or you can read a copy of it online here.

Finally, check out this wonderful animated version of the story narrated by James Mason. His rendition of the madman is strikingly similar to the one in my head! Be warned though, that even though it is excellently rendered and recited, this story is slightly abridged from Poe’s original masterpiece.